Occasionally, even the most impenetrable of exteriors reveal their cracks, and when we peer through, we may glimpse a kind of fragility which we thought only to have resided in ourselves. One of my favourite tutors, John Roe, wrote a book called Shakespeare and Machiavelli, and in analysing Machiavelli's advice that a prince should not reach for the moral option when time permits no leisure to contemplate or reflect it, but rather do what is expedient, John has this to say:

It is difficult to resist the appeal of Machiavelli's argument at moments such as these: those of us who will never aspire to princely power still know what it is to be confronted with awkward choices, and find ourselves sometimes losing sight of the moral perspective because a moment of ethical blindness happens to be convenient. If only, we might say to ourselves, we could do this and get away with it - not just in the eyes of the world but also in our heart of hearts. (1)

Without reading too much into an admired tutor, I think it is fair to say that things weighed on John Roe's mind as he wrote these words. As a very majestic, outwardly gentle and unshowy man, it comes as some surprise to find a darker side must lurk beneath. That is what makes a man fascinating. It reminds me very much of something he once said in class, discussing Angelo in Measure for Measure:

We have all been there, haven't we? Where there's something you're thinking of doing and you say to yourself 'I want to do it...I shouldn't do it, and I know I shouldn't do it - but you know, I think I'm going to do it!' (2)

This approach is one of someone who responds to what he reads: rather than taking Machiavelli as pure theory, he allows the theory - the words - into his imagination, applying them to real life, and thereby bringing the ideas into life. What fascinates me is how we respond differently to different things. This idea of Machiavelli's clearly took life John Roe's imagination, but I have to confess it doesn't really take any in mine (though John's re-expression of it is certainly delicious).

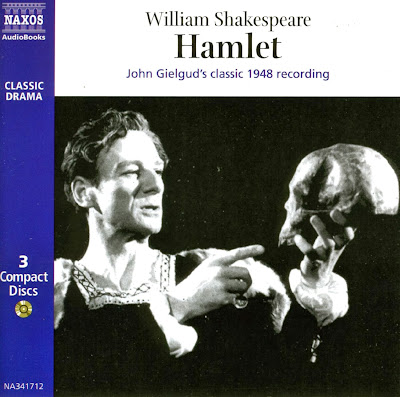

That is not to say my imagination be barren, for it is not. I have found lately that something similar has happened to me, with Sir John Gielgud. It is so rare to find writing which makes one feel one really understands the thoughts and the feelings that have produced it, but that is exactly how I feel when I read what are the most intimate of all expressions: those he puts in a letter. This is to his lover, Paul Antsee on the 1st of August, 1959, London:

Silly one - cruel one - you devestated me last night, and I couldn't sleep and you never rang even when you got home, dreading, I suppose, our usual fruitless arguments with the long empty pauses in between. Yes, of course, you know me only too well (but just not all that well as you think you do).

I shall always love you, but your sudden turns from sweetness to venom rather terrify me, though in a way I understand, being somewhat (and lamentably) senior. (3)

What strikes me is how the course of Gielgud's thoughts and feelings are so undisguised. He begins with anger, without making any accusations: Antsee has been cruel, but Gielgud only relates what Antsee's cruelty has done to hurt him, rather than trying to return any cruelty. Then he sounds the retreat, sharing in the blame for the awkward telephone calls, making Antsee's excuses for him. Then, he sounds an awkward peace, conceding that Antsee knows him well, yet denying him the full satisfaction of his own presumptions. The next line moves in much the same way, pointing the finger at Anstee's venom before retreating again, on account of his seniority. The tension is palpable, between the mix of self rebuke and hurt and anguish with tenderness, conciliation and love. How many of us have felt such a mix? Those of us who have will understand the conflict of feeling that lies behind each word.

Yet, I cannot pretend for a moment that I really understand what Gielgud was feeling as he wrote these words, just as John Roe has to concede in his response that he is not a man for whom such an idea was really intended. I have no idea what the fight was about, what kind of a man Antsee might have been or how the necessarily clandestine nature of gay relationships in the 1950s would have affected such a dynamic. Gielgud had been arrested and humiliated in 1953 for his sexuality, and never quite got over the shame of it: in how much fear, then, did such a couple exist? I cannot begin to guess. What I see in his words are not his feelings, but my own feelings grafted thereon, woven therein.

To be confessional for a moment, my little analysis above, though objective, is really how I feel when I feel a grievance: I want to say how much he has hurt me, yet I know the fault of it really to lie with me. Thus, Gielgud's words are not so much a portal into his soul, but a mirror for mine, someone else's words that I have found which perfectly capture something inside of me.

That leaves me to wonder a moment. Most people who come across this letter will not really respond to it. That is for no reason other than that we all respond so very differently to certain things, and not at all to much else. By way of example, abstract painting leaves me absolutely cold but enthralls others. What is it, then, that I am actually responding to? Is it the feeling the words express, or the expression itself? If I found an abstract picture that expressed the same feeling, it would produce an entirely different one in me (I suspect one of disdain). Whatever the answer, as I began this piece by suggesting, sometimes one's reaction to something can be telling in ways one can never suspect. I wonder what John Roe would make of my response to his response? I suspect he would say that, though he is no prince and I am no 1950's closeted actor, we may still gain access to what lies behind the words.

(1) John Roe, Shakespeare and Machiavelli (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2002), p. 16.

(2) In the same class, John showed amusing relish for the Duke's villainous gambit in the final scene, where he offers to kill Angelo on Isabella's command.

(3) Sir John Gielgud: A Life in Letters (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2005).

It is also oddly un-poetic. I confess I am overtly treading on the subjective here, and aesthetics are difficult to turn into more than matters of personal taste. However, there is a practical measure to my objection. The first is that aesthetics - sheer beauty - can have a mesmeric effect on the pupils. Such moments as Caliban's speech - one of two poetic high points - had the pupils captivated either when I recited it myself, or when I called upon trusty old Gielgud to do it for me. Moreover, those plays in which Shakespeare more carefully observes the rigours of meter are thereby more fertile plains for teaching iambic pentameter (plus other styles), which besides anything else is something pupils need to know for the poetry and Shakespeare components of the GCSE.

It is also oddly un-poetic. I confess I am overtly treading on the subjective here, and aesthetics are difficult to turn into more than matters of personal taste. However, there is a practical measure to my objection. The first is that aesthetics - sheer beauty - can have a mesmeric effect on the pupils. Such moments as Caliban's speech - one of two poetic high points - had the pupils captivated either when I recited it myself, or when I called upon trusty old Gielgud to do it for me. Moreover, those plays in which Shakespeare more carefully observes the rigours of meter are thereby more fertile plains for teaching iambic pentameter (plus other styles), which besides anything else is something pupils need to know for the poetry and Shakespeare components of the GCSE.